Against Goodness: instituting against huma(nitaria)nism @ The Perennial Biennial, Ljubljana

Talk and discussion on the institutionalisation of goodness and its consequences.

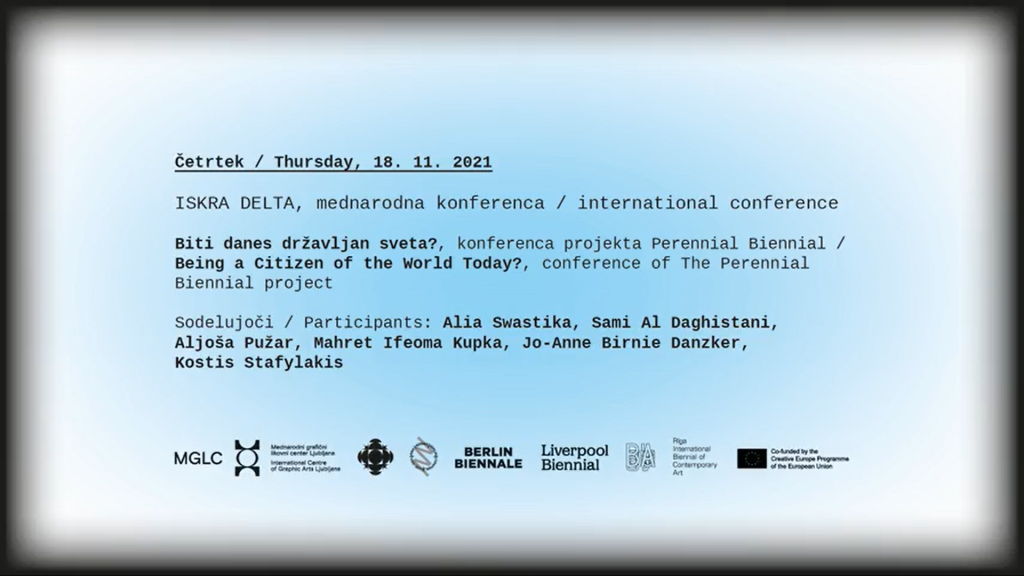

In the framework of the Perennial Biennial's conference, "Being a Citizen of the World Today?," at MGLC Švicarija. Ljubljana,, 18 November 2021.

About the conference:

𝗔𝗹𝗶𝗮 𝗦𝘄𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗸𝗮, 𝗦𝗮𝗺𝗶 𝗔𝗹 𝗗𝗮𝗴𝗵𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗻𝗶, 𝗔𝗹𝗷𝗼š𝗮 𝗣𝘂ž𝗮𝗿, 𝗠𝗮𝗵𝗿𝗲𝘁 𝗜𝗳𝗲𝗼𝗺𝗮 𝗞𝘂𝗽𝗸𝗮, 𝗝𝗼-𝗔𝗻𝗻𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗿𝗻𝗶𝗲 𝗗𝗮𝗻𝘇𝗸𝗲𝗿, 𝗞𝗼𝘀𝘁𝗶𝘀 𝗦𝘁𝗮𝗳𝘆𝗹𝗮𝗸𝗶𝘀

An excerpt from my talk:

Against Goodness Instituting beyond humanitarianism

In July 2017, e-flux and Stenberg Press published the collective volume What’s Love (or Care, Intimacy, Warmth, Affection) Got to Do with It? claiming that “What we can no longer get from the state, the party, the union, the boss, we ask for from one another.” The editors explain that ‘It is often said that we no longer have an addressee for our political demands. But that’s not true. We have each other.’ In September 2020, the Philadelphia Museum of Art hosted the Art and Care show, an exhibition examining the ways “artists over the last century have pictured and envisioned acts of caregiving as observers, practitioners, patients, and activists”. As the exhibition blurb suggests “At a time when the stakes of such struggles are higher than ever, the pictures gathered here speak to the many forms of care that health, healing, and human dignity require.” Also in September 2020, the Yale MacMillam Centre, opened “Visual Acts of Radical Care: An Exhibition of Feminist Artists-Activists from Central and Eastern Europe”. The show focused on Central and Eastern Europe authoritarian regimes that silence artists, expel NGOs, and debilitate social movements”, while striving to envision an “allyship amongst ethnically, racially, religiously varied communities” acting with “radical care.” In October 2020, the Temporary Art Platform, a curatorial project with emphasis on the Global South, presented Make yourself at home: radical care and hospitality, a program conceived to provide immediate support to artists and cultural practitioners who were impacted by the Beirut Port explosion on August 4. It focused on “care and hospitality as driving forces for collective solidarity, togetherness, generosity and hope in a context of the suffocating deadlock we are facing globally…”. In October 2020, the Badischer Kunstverein organized an extensive series of performances, workshops, lectures and discussions titled “How do we care? A series of programs to politicize bodies and alternative concepts of care”. As the organizers explain, “The program questions the fragility and resistance of bodies in times of a pandemic and examines alternative and radical ways of providing care and assistance.” In May 2021, the Berlin Biennale announced the appointment of multi-talented artist Kader Attia as artistic director of the 12th iteration. The biennale’s announcement explains that Attia works with the notion of repair—first of objects and physical injuries, and subsequently of individual and societal traumas- and describes the upcoming show as a “critical conversation about how to care for the now.” In June 2020, The Ruangrupa collective, appointed artistic directors for Documenta fifteen, announced the topic of lumbung as the title and theme of the upcoming show. The Lumbung is a traditional Indonesian rice barn that stands for the “shared use of resources and mutual care”. Lumbung is the centre of a community whose members care for each other and take responsibility together.

I must say that I feel happy that an intersectional understanding of care has entered the art-field so strongly but I also feel I need to ask myself why such an overwhelming adoption of the theme of care by all sorts of institution and cultural initiatives. And how is this idea of the “caring institution” connected to the way institutions and art projects have portrayed themselves throughout the years of the financial crisis, with notions such as the commons, resilience, the epistemologies of the Global South being pivoted in this process of self-discovery. I think we’ll fail to assess this process if we miss this specific shift in the discourse of the institution, the curatorial, the art initiative: In the texts I quoted I sense this turn from the civil institution (the union, the party, the state, the labor organigram) towards “one another”- towards our-selves as individual agents, “humans” abandoned in this deregulated havoc. “We have each other”, the e-flux book tells us. And it is in this shift that I see a recurrence of a certain humanism that troubles me a bit. In the shift to “one another” the appeal to the party, the state, the parliament, is not entirely obfuscated but rather substituted with an appeal to the art institution or art project as the Big Other that replaces and “salvages” all discredited social institutions of our recent past. Practicing and teaching care seizes to simply pertain to a strategic social process by relies on the innate human goodness of oneself (or of ethnically aligned communities). Today, I want to share with you the hypothesis, that this appeal to goodness does not necessairily help art’s emancipatory agenda since it quite often overlooks the diverse dependencies of peripheral and precarious institutions. Imposing itself as a universal virtue, Goodness (or community, or togetherness, or “having each other)” does not immediately foster the progressive restructuring of dislocated social sphere. And, this is perhaps a lesson from Athens.

View my talk here, from 52 min to 1.35 min.